Why We Get Fat – and What to Do About It by Gary Taubes: A Comprehensive Review

The question of why we get fat has haunted modern society for decades. Governments issue dietary guidelines, doctors prescribe calorie restriction, and fitness industries thrive on the promise of fat loss. Yet obesity rates continue to climb relentlessly. In Why We Get Fat – and What to Do About It, investigative science journalist Gary Taubes dismantles the conventional wisdom surrounding weight gain and replaces it with a provocative, evidence-driven explanation rooted in biology rather than moral failure.

This book is not merely about diet. It is an indictment of decades of flawed nutritional science. Taubes argues that why we get fat has little to do with gluttony or sloth and everything to do with hormones—particularly insulin—and the carbohydrates that stimulate it.

The Calorie Myth: Why “Eat Less, Move More” Fails

For generations, the dominant explanation of why we get fat has been painfully simplistic: consume too many calories and burn too few. Taubes exposes this theory as not only inadequate but scientifically unsound.

Calories do not act independently of the body’s hormonal environment. Two diets with identical caloric values can produce radically different outcomes depending on their macronutrient composition. According to Taubes, the body is not a passive calorie-counting machine; it is a hormonally regulated system that decides whether calories are burned or stored as fat.

This insight fundamentally reframes why we get fat, shifting blame away from personal discipline and toward metabolic dysfunction.

Insulin: The Master Regulator of Fat Storage

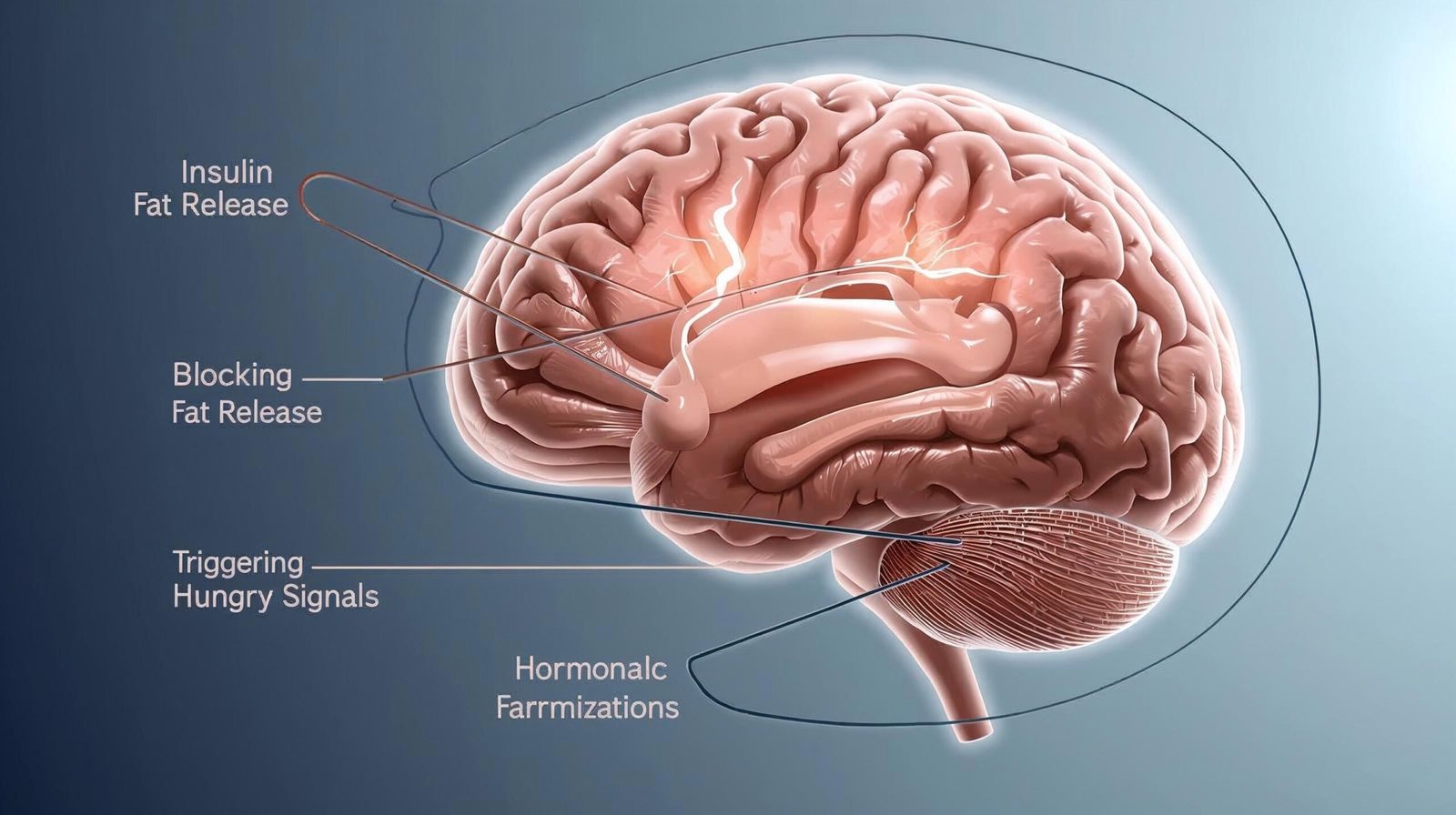

Central to Taubes’ thesis on why we get fat is insulin, a hormone responsible for regulating blood sugar and fat storage. When carbohydrates—especially refined sugars and starches—are consumed, insulin levels rise. Elevated insulin instructs the body to store fat and prevents fat from being released for energy.

Thus, fat accumulation is not the result of overeating but the cause of hunger itself. As insulin locks fat inside adipose tissue, the body experiences an energy deficit, triggering hunger and lethargy. This biological trap explains why we get fat even when eating “normal” amounts of food.

Carbohydrates, Not Fat, Are the Primary Culprit

One of the most controversial claims in Why We Get Fat is that dietary fat is not responsible for obesity. For decades, fat was demonised as the enemy of health. Taubes systematically dismantles this belief, citing historical, epidemiological, and experimental evidence.

Populations that consumed high-fat diets—such as traditional Inuit communities—exhibited negligible rates of obesity and diabetes. Conversely, societies that adopted carbohydrate-heavy Western diets experienced dramatic increases in weight gain. This pattern reinforces Taubes’ core argument about why we get fat.

The Historical Failure of Nutritional Science

Taubes devotes considerable attention to exposing how flawed science became entrenched dogma. Poorly designed studies, political influence, and confirmation bias led to the vilification of fat and the promotion of carbohydrate-rich diets.

As a result, public health policies inadvertently worsened the obesity epidemic. Understanding this historical context is essential to grasp why we get fat despite widespread adherence to official dietary advice.

Obesity Is Not a Moral Failing

Perhaps the most humane contribution of Taubes’ work is the removal of moral judgement from body weight. According to Taubes, obesity is a physiological condition, not a behavioural defect.

People do not get fat because they are lazy or weak-willed. They get fat because their hormonal environment forces fat storage. This compassionate framing of why we get fat has profound implications for mental health, self-worth, and medical treatment.

What to Do About It: The Low-Carbohydrate Solution

After meticulously explaining why we get fat, Taubes turns to the practical question: what can be done?

The solution is not calorie restriction but carbohydrate restriction. By reducing sugars and refined starches, insulin levels decline, allowing fat to be released and burned for energy. Hunger diminishes naturally, and weight loss becomes a metabolic consequence rather than a constant struggle.

This approach aligns with ketogenic and low-carbohydrate dietary models, which have demonstrated remarkable success in reversing obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Why Exercise Alone Is Not the Answer

While physical activity is beneficial for overall health, Taubes challenges the belief that exercise is an effective primary tool for weight loss. Exercise does not address the hormonal mechanisms behind why we get fat.

In many cases, increased activity simply increases appetite, leading to compensation through food intake. Without addressing insulin-driven fat storage, exercise becomes an inefficient and frustrating solution.

Medical Resistance and Institutional Inertia

Despite mounting evidence, the medical establishment has been slow to embrace Taubes’ conclusions. Entrenched beliefs, financial interests, and professional reputations have created resistance to change.

This institutional inertia explains why outdated advice continues to dominate public discourse on why we get fat, even as obesity-related diseases reach epidemic proportions.

Scientific Evidence Supporting Taubes’ Claims

Since the publication of Why We Get Fat, numerous studies have validated Taubes’ arguments. Low-carbohydrate diets consistently outperform low-fat diets in terms of weight loss, metabolic health, and patient adherence.

These findings reinforce the biological explanation of why we get fat and challenge the calorie-centric paradigm that has failed millions.

Who Should Read This Book?

This book is essential for:

-

Individuals struggling with chronic weight gain

-

Medical professionals seeking deeper metabolic insight

-

Fitness enthusiasts questioning conventional advice

-

Anyone interested in understanding why we get fat beyond surface-level explanations

The Psychological Cost of Nutritional Misinformation

Beyond the physiological damage inflicted by flawed dietary advice lies a quieter but equally destructive consequence: psychological exhaustion. Decades of being told that weight gain is a personal failure have produced a culture of shame, guilt, and chronic self-blame. Gary Taubes’ work indirectly exposes how nutritional dogma has harmed not only bodies but minds.

When individuals believe they are solely responsible for their inability to lose weight, repeated failure erodes confidence and fosters disordered relationships with food. Cycles of deprivation and relapse become normalised. Understanding why we get fat through a biological lens offers something profoundly restorative—it replaces shame with comprehension.

This shift is not cosmetic. It alters how individuals approach eating, health, and self-discipline. Knowledge does not merely inform; it liberates.

Hunger as a Biological Signal, Not a Weakness

Modern dieting culture treats hunger as an enemy to be conquered. Taubes reframes hunger as a legitimate biological signal, distorted by hormonal imbalance rather than excess indulgence. When fat is locked away by elevated insulin levels, the body experiences internal starvation, regardless of visible adiposity.

This distinction is critical. It explains why willpower-based dieting fails over time. Hunger is not a negotiable emotion; it is a survival mechanism. Ignoring it leads to metabolic slowdown, muscle loss, and eventual rebound weight gain. The failure to recognise this truth has perpetuated ineffective strategies and reinforced misconceptions about self-control.

Relearning how to interpret hunger is central to resolving why we get fat at a functional level.

The Misuse of Epidemiology in Nutrition Science

One of Taubes’ most incisive critiques lies in his exposure of epidemiological studies masquerading as definitive proof. Correlation-based research has long been used to justify sweeping dietary recommendations, despite its inability to establish causation.

For example, populations consuming low-fat diets were assumed to be healthier, without accounting for confounding variables such as smoking rates, socioeconomic status, or industrial food exposure. These methodological flaws were not minor oversights; they shaped global dietary policy.

This misuse of data has contributed significantly to public misunderstanding and continues to obscure the true drivers of obesity. Taubes’ insistence on controlled experimentation over observational inference represents a necessary correction to a deeply compromised field.

Industrial Food and the Economics of Obesity

Any serious discussion of modern health must confront the role of industrial food production. Highly processed carbohydrates are not merely dietary choices; they are economic products engineered for profit, shelf stability, and hyper-palatability.

Refined grains and sugars dominate food systems because they are inexpensive to produce, easy to transport, and aggressively marketable. Their metabolic consequences, however, are devastating. Frequent insulin stimulation, disrupted satiety signalling, and addictive consumption patterns are not accidental side effects but predictable outcomes.

This industrial framework reinforces the mechanisms behind why we get fat, creating an environment where metabolic dysfunction becomes the default rather than the exception.

The Medicalisation of Symptoms Instead of Causes

Another disturbing trend illuminated by Taubes’ work is the medical community’s reliance on symptom management rather than causal resolution. Obesity-related conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidaemia are routinely treated with pharmaceuticals, while dietary drivers remain unaddressed.

This approach offers temporary biochemical control but fails to reverse underlying pathology. Patients accumulate prescriptions without achieving genuine metabolic recovery. In contrast, dietary carbohydrate reduction addresses the hormonal origin of these disorders directly.

By confronting why we get fat at its source, Taubes implicitly challenges a healthcare model overly dependent on chronic medication.

Cultural Resistance to Paradigm Shifts

Scientific revolutions rarely occur without resistance. The persistence of calorie-centric thinking reflects not ignorance but institutional inertia. Careers, reputations, and entire industries have been built upon the prevailing model. Admitting error carries professional and financial consequences.

Taubes’ work threatens this stability, which explains the hostility it has often encountered. Yet history demonstrates that scientific progress frequently emerges from such discomfort. The rejection of outdated models is not a failure of science but its fulfilment.

True understanding of why we get fat requires intellectual courage—the willingness to abandon comforting simplifications in favour of complex truths.

Individual Variation and Metabolic Diversity

One of the most misunderstood aspects of weight regulation is individual variability. Taubes acknowledges that metabolic responses to carbohydrates differ among individuals. Genetics, early-life nutrition, stress, and sleep patterns all influence insulin sensitivity.

This diversity explains why universal dietary prescriptions fail. What works for one person may be ineffective—or even harmful—for another. Recognising this variability does not weaken Taubes’ argument; it strengthens it by rejecting one-size-fits-all solutions.

Understanding why we get fat demands respect for biological individuality rather than blind adherence to standardised guidelines.

Long-Term Sustainability and Dietary Adherence

Critics often argue that low-carbohydrate approaches are unsustainable. Taubes counters this by pointing out that sustainability depends on hunger regulation. Diets that suppress hunger through hormonal balance are inherently easier to maintain than those reliant on perpetual restraint.

When insulin levels stabilise and fat becomes accessible for energy, appetite normalises. Meals become satisfying rather than restrictive. This physiological ease explains the long-term adherence observed in many carbohydrate-restricted populations.

Sustainability, therefore, is not a matter of motivation but metabolic alignment.

Implications for Future Public Health Policy

If Taubes’ conclusions were fully integrated into public health strategy, the implications would be transformative. Dietary guidelines would prioritise carbohydrate quality and insulin management rather than caloric arithmetic. Food labelling would reflect hormonal impact, not just energy content.

School nutrition programmes, hospital meals, and community interventions would shift away from low-fat dogma. Such reforms could dramatically reduce obesity-related disease burden and healthcare expenditure.

Reframing why we get fat is not merely an academic exercise; it is a policy imperative.

A Call for Intellectual Honesty

Perhaps the most enduring value of Why We Get Fat – and What to Do About It lies in its demand for intellectual honesty. Taubes does not claim infallibility; he invites scrutiny, debate, and further research. What he rejects is complacency—the quiet acceptance of ideas that demonstrably fail.

In an era overwhelmed by nutritional noise, this commitment to evidence over ideology is refreshing. Readers are encouraged not to memorise rules but to understand mechanisms. This approach cultivates autonomy rather than dependence.

Reclaiming Authority Over Personal Health

One of the most overlooked consequences of flawed nutritional narratives is the erosion of personal agency. When individuals are repeatedly told to obey rigid dietary rules that contradict their lived experience, trust in both science and self gradually diminishes. Confusion replaces confidence, and health becomes an external prescription rather than an internal understanding.

Gary Taubes’ work implicitly restores that lost authority. By encouraging readers to question assumptions, examine evidence, and observe physiological responses, he shifts the locus of control back to the individual. This intellectual empowerment is especially valuable in an age dominated by algorithm-driven advice and commercialised wellness trends.

True health literacy does not arise from memorising food lists or following fashionable regimens. It emerges from comprehension—knowing how the body responds to different stimuli and adjusting behaviour accordingly. Such an approach fosters resilience rather than dependence, adaptability rather than rigidity.

Moreover, this framework invites long-term thinking. Instead of pursuing rapid transformations fuelled by desperation, individuals are guided toward sustainable habits grounded in biological reality. Meals become sources of nourishment rather than negotiation, and eating regains its rightful place as a supportive act rather than a moral test.

In this sense, the book transcends dietary debate. It serves as a reminder that progress, whether in health or knowledge, demands scepticism, patience, and humility. When evidence is allowed to challenge belief, genuine improvement becomes possible—not only in body composition, but in the quality of one’s relationship with health itself.

Final Reflection

The enduring power of Gary Taubes’ work lies in its clarity. By stripping away moral judgement, exposing scientific error, and centring biology, he provides a coherent explanation for a problem long obscured by confusion.

To grasp why we get fat is to reclaim agency over health decisions, free from guilt and misinformation. It is an invitation to think critically, eat consciously, and demand better science from those who shape public discourse.

At shubhanshuinsights.com, we believe that progress begins where dogma ends. This expanded exploration reinforces a simple but profound truth: sustainable health emerges not from fighting the body, but from understanding it.

FAQs

1. What is the central idea of Why We Get Fat?

The book explains why we get fat through hormonal regulation, particularly insulin, rather than calorie imbalance.

2. Does Gary Taubes recommend counting calories?

No. Taubes argues that calorie counting ignores the biological mechanisms behind why we get fat.

3. Is fat consumption safe according to the book?

Yes. Taubes presents strong evidence that dietary fat does not cause obesity.

4. Can this approach help with diabetes?

Absolutely. By addressing insulin resistance, the book offers solutions to both obesity and type 2 diabetes.

5. Is exercise useless for weight loss?

Exercise is healthy, but it does not solve why we get fat without dietary change.

Conclusion: A Necessary Revolution in Thinking

Why We Get Fat – and What to Do About It is not a diet book; it is a scientific reckoning. Gary Taubes compels readers to abandon decades of nutritional misinformation and confront the uncomfortable truth about why we get fat.

This book empowers readers with knowledge, relieves them of misplaced guilt, and offers a rational path toward lasting health. In a world drowning in dietary confusion, Taubes provides clarity grounded in evidence and logic.

At shubhanshuinsights.com, we believe that true transformation begins with truth. Understanding why we get fat is not merely about losing weight—it is about reclaiming autonomy over one’s health, free from dogma, shame, and ineffective advice.

If there is one book that deserves a permanent place in the modern health discourse, this is it.